Of all the training questions I’ve had over the years, this one has plagued me the most in one form or another. I’d have these beautifully laid-out plans of run, swim and bike workouts all spaced out perfectly for recovery purposes, and then I’d remember I had to get strength in there somehow and the whole week would get screwed up. Was I supposed to do that the same day as a hard workout? Next day? How many reps?

Up until last week I thought I’d got that figured that out. In my running and triathlon days, endurance was the name of the game. The objective of strength work in the gym was to buffer against injury and increase resistance to fatigue. This is also called building “muscular endurance” and is typified by sets with relatively higher reps and lower weights. Coming into workouts with some muscle fatigue is normal, provided recovery is adequately accounted for.

Such strength work fits in nicely with a classic pyramid training plan which starts with a “base” period where you build your basic fitness – get an aerobic base, build strength as described above, and work on “speed skills” i.e. sport-specific drills where you work on technique and cadence to help you gain efficiency. As base progresses to “build” and “race” phases, longer and/or harder sport-specific workouts take precedence, and strength work in the gym goes on the back burner. I’d normally find that during springtime I’d hit a week where I’d get really fatigued trying to do a lot of everything and crash. This was my signal it was time to cut back strength to once-a-week maintenance. Perfect.

This off-season however, three things are different. First, I’m bike racing, not triathlon-focused. Second, I got flexible and strong enough to start lifting some proper heavy weights. Third, my coach flipped the classic pyramid on me. This means we’ve been working on my limiter – the short end of the power curve – with hard interval workouts during my “base” period.

Always the one to push, of course I tried to “Keep Calm and Do Everything”. I need to do strength or I’ll be weak! Going into hard intervals fatigued? Well that’s normal, isn’t it? Doesn’t that just mean I’ll ultimately be stronger? I checked with my coach and my trainer.

Coach (still getting used to me): “Uhhhhh no, I need you fresh for the hard stuff. Sorry…why did you put an extra strength workout in your plan?”

Trainer (known me for years): “No. LOL, you always try to do too much, you’re hilarious…”

OK then…time to go away and figure out where my thinking went wrong. Here’s a summary of what I learned.

Wikipedia defines muscle fatigue as follows: “Muscle fatigue is the decline in ability of a muscle to generate force. There are two main causes of muscle fatigue: the limitations of a nerve’s ability to generate a sustained signal (neural fatigue) and the reduced ability of the muscle fiber to contract (metabolic fatigue).” Metabolic fatigue is caused by two main factors: shortage of fuel and/or accumulation of metabolites (e.g. lactic acid) within the muscle fibers.

Strength can be defined as the “property of a person or thing that makes possible the exertion of force or the withstanding of strain, pressure, or attack”. Strength training is about developing the ability to generate force. That force can be generated by one or more of three types of muscle fibers: “slow-twitch” – Type I, or “fast-twitch” – Types IIa and IIb. Essentially, slow-twitch fibers use oxygen for fuel – i.e. they work “aerobically” – and this type of fueling allows the fibers to generate a moderate level of force for a sustained amount of time. Put another way, they are recruited when muscular endurance is required. Fast-twitch fibers use stored muscle glycogen for fuel instead of oxygen – i.e. they work “anaerobically”. Anaerobic fueling allows the fibers to generate high-intensity force, but only for a short period of time. They are recruited in order to generate power. Fast-twitch fibers only contract once the slow-twitch fibers have fatigued.

The percentage of each type of fiber in your body depends on both genetics and how they are developed in workouts. As explained by my trainer: “different strength workouts are specifically measured by Time Under Tension, Duration, Repetition, Load, and Speed. Relying on these measurements illustrates how the workout is defined and which muscle fibers you’re firing off.” The table below summarizes the differences between them in more detail.

Characteristics of muscle fiber types

| Characteristic | Type I | Type IIa | Type IIb |

| Contraction speed | Slow | Fast | Fast |

| Resistance to fatigue | High | Medium | Low |

| Force production | Low | High | High |

| Glycolytic capacity (ability to produce energy in the absence of oxygen) | Low | High | High |

| Oxidative capacity (ability to use oxygen as fuel) | High | Medium | Low |

| Recruitment during sport | Endurance | Mix | Power |

Going back to the original question, then, where was my thinking going wrong? – Essentially, I was confusing the development of endurance and power. Type II muscle fibers won’t fire when they are fatigued, which means that if I head into an interval workout with sore muscles, I will recruit more of the Type I rather than Type II. This isn’t an absolute – depending on level of fatigue I may end up using some percentage of all types – but if the objective of the workout is to train power generation, it’s definitely less effective.

There is some nuance when it comes to putting a training plan together. One thing that I did notice and is apparently a common experience, is that I can cope with two hard workouts on back-to-back days with only a small loss in power. After that I’m toast, but provided I get adequate recovery before the next hard session, it’s OK. Again reviewing this with my trusty coach/trainer team, it seems this ability to cope with back-to-backs is really personal to each athlete. I’ve been training for many years now so maybe my overall resistance to fatigue has developed over time. In addition, one needs to consider the cumulative impact of workouts, not just what you did the day before. Two hard days at the end of an intense training block likely feels quite different than at the start.

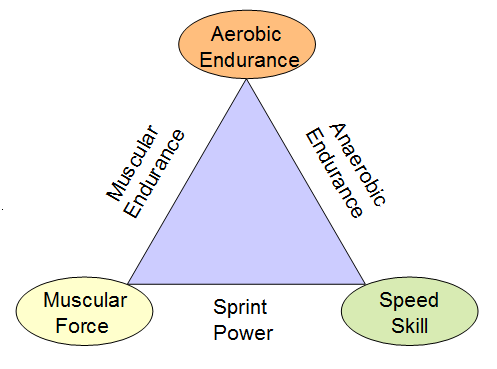

All the concepts above come together nicely in the diagram below, which is the well-known “6 abilities” triangle as used by Joe Friel in his Training Bible books.

Each of the advanced abilities shown on the sides depends on the basic abilities shown in the corners. In particular: muscular endurance lies between the development of force and aerobic endurance. It’s the capacity to maintain a relatively high force for a relatively long time. Muscular power lies at the intersection of force and rpm – Force * Cadence = Power.