I recently did a mountain bike race with a friend, who had crashed out and quit part way through. When I found out that the crash hadn’t precluded him from carrying on, I innocently asked why he’d stopped, and he got defensive about it. So then I asked him why he was getting so defensive (I can be really annoying), and he said he didn’t know – since the only reason was that he’d just felt done for the day and had nothing to gain by carrying on.

Another friend of mine quit a trail marathon a while back. When I asked her why, she said she had good reason – it was a C race for her, it was pouring down, she was soaked head to toe and freezing just a few miles in and just didn’t think it was fun anymore. She quit out of misery; she knows it was the right thing for her to do at the time; but she’s still “bummed I quit”.

The one and only time I’ve ever quit a race was at the CRCA Bear Mountain Classic, in 2018. I lined up at the start in a cesspool of negativity – tired, coming off a string of bad races, and fully expecting to “fail” (hills aren’t my thing). No more than 15 minutes later I’d got dropped on the first hill and stopped biking, my heart pounding through my chest, my mind and body crushed with defeat. I saw my husband riding towards me and, with tears of failure welling up inside, turned off the course and into the comfort of his draft.

Were my friends wrong to quit? Was I wrong to quit? Why?

To put my conclusions first: no; yes; and, depends on what and why you’re quitting.

What are you quitting: by which I mean, what was your goal to begin with? What improvement were you trying to make? Are you quitting an outcome, or the journey?

For example, let’s suppose it’s for a specific placing. Pros quit races all the time. If their goal is to finish in the money and quitting on a bad day means they save their body for a good one, then that makes sense.

On the other hand, let’s suppose your goal was to finish a race as best you can. Do you want to quit because you think you have “failed” your goal? Then – even if you’re missing a hoped-for time or placing – then quitting can often deprive you of a perfectly good learning opportunity. If it’s so hot you can barely think, or your legs are so tired you’re pedaling squares, or that nasty mid-race hill gets the better of you, then maybe it’s worth figuring out how to deal with that. What does your body and mind need to be able to get through those circumstances? Adversity is a great teacher, and in my view at least, the better someone can manage adverse conditions, the more respect they deserve as an athlete.

Why are you quitting: are you physically suffering to the point where if you continue you could get sick or injured? If yes, then quit. Are you suffering in a way that will ultimately have negative, not positive repercussions – i.e. the suffering outweighs any benefits you could possibly hope to get out of the race? If yes, then quit.

Do you have that voice in your head that says, “I just can’t do it. I need to stop”? If yes, then hold on. As postulated by the central governor theory your brain will signal you to stop as a way to protect your body. Put another way, allow for the potential that you can do more than you thought. Are you quitting because you feel miserable and defeated? If yes, then hold on. Learn to pick yourself up off the road. Look for solutions to keep going. Stay positive.

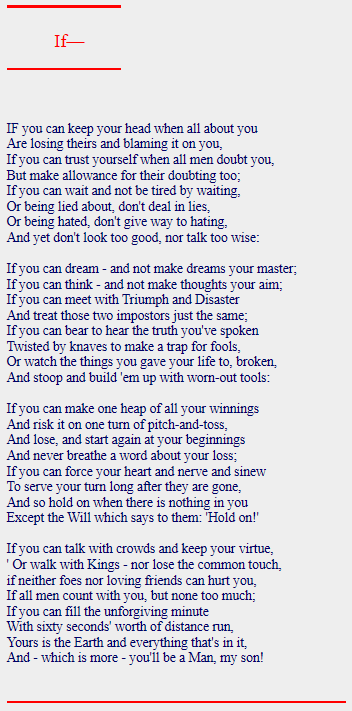

To quote from the poem “If”:

If you can force

your heart and nerve and sinew

To serve your turn long after they are gone,

And so hold on when there is nothing in you

Except the Will which says to them: ‘Hold on!’

Back to the opening examples.

My first friend is an expert mountain biker. He was in the race to win and at the same time had nothing to prove, having won it the year before. The crash was bad – it took him a decent amount of time to figure out how far he’d somersaulted from his bike, make his way back to the start, un-mangle his bike handlebars and get back on. Was he fine to continue, medically speaking? Yes. Could he have gained some incremental fitness benefit by carrying on? Sure. Did he demonstrate a lack of tenacity by not doing so, thereby rendering himself a “bad quitter”? Hell no. Tenacity is his middle name. He simply felt somewhat shaken by the crash and didn’t have his head in the game after that.

My second friend is a top age group Ironman competitor and also tough as nails. It would have been great if she’d completed the race, as it was a new experience and a perfect early-season fitness-builder. But if you’re at the point where you’re so cold you’re physically unable to push your body in a healthy way, then seriously, just stop already. And if you’re not having fun in a race where your primary goal was, in fact, to have fun, then how about you just table it for another day…

I was at the start line of a race that would have increased my fitness had I worked hard and finished, whether on the back, off the back, or even waaay off the back for that matter. I had come to the start line defeated before I took my first pedal stroke and failed to find the mental fortitude to overcome it. Worse still, my misery was driven not by physical discomfort or injury, but by a narcissistic and misplaced presumption that being off the back would be utterly shameful.

To quote “If” again:

If

you can meet with Triumph and Disaster

And treat those two impostors just the same…

Right on. I quit because I was unable to do that. That was a fail.

In the end, I really like the way my coach puts it: you need to find “just the right amount of striving”. Not so little that you throw away the potential for gain; not so much that vainglory trumps real achievement.